US stock market exceptionalism: stick, twist - or fold?

The S&P 500 is down in Q1 - the end of a correction, or just the end of the beginning of something bigger?

In 1923, John Maynard Keynes described the largely-peaceful period between the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815) and the start of World War I (1914) as a golden age for investing and compound interest which “made possible the material triumphs which we all now take for granted”. Saving and investing became “a duty and a delight”, meaning “God and mammon were reconciled”1.

By 1923 though, war and inflation had halved the real value of the 2.5% Consol (Britain’s principal government bond) versus its pre-war level. “The whole of the improvement of the nineteenth century had been obliterated, and his [the bondholder’s] situation was not quite so good as it had been after Waterloo”2.

The First World War marked the beginning of the end of Britain’s dominance of global credit and the financial markets, and with it, the central role of the pound as the currency of global trade.

While the near 10% sell off in the US S&P 500 from its highs isn’t quite so dramatic, the character of the price action in the last few months is worth examining for one simple reason: is this a dip to be bought, or a sign of a more secular change in asset allocation?

In recent years, periods of ‘risk off’ in markets have been characterised by a general sell off in equities, bonds, credit and commodities with the only ‘asset’ showing any real strength being the US dollar as it rose against all currencies, including gold. Such sell-off’s have generally been short and sharp, with high levels of volatility, and often ending in a central bank intervention if serious enough (think Q4 2018 or Q1 2020 during Covid). Markets have always subsequently bounced.

Q1 2025 has been a little different. While the S&P 500 is down nearly 4% year to date, Germany’s Dax index is up nearly 16% during the same period, despite the collapse in the country’s industrial base and consumer confidence. With the total S&P 500 correction at around 10%, the VIX volatility index has not risen above 30, the first time a sell-off of such size in less than a month’s trading has led to such a paltry rise in implied market volatility.

Rather than selling off, bond yields in the US have fallen, with the 10yr Treasury down 30 basis points in Q1. Most importantly, despite the risk off, the DXY dollar index is down 4.2% year-to-date. Gold is up 15% on the year as well.

There is a lot to unpack here. The fall in 10yr Treasury yields may indicate a higher chance of a 2025 recession in the US . This is especially true given 2yr yields have also fallen nearly as much. Markets are still however pricing just two more Fed rate cuts this year.

The poor stock market performance and the reversal of some of the euphoric bitcoin rally of late 2024 might in part be a sense of realism returning to markets. While President Trump’s election saw stocks immediately price-in tax cuts and bitcoin anticipate a new sovereign crypto fund, the potentially negative effect of tariffs and DOGE were there to be seen if one cared to look (see Market Depth’s comment from November last year, link above).

There is much talk at present of the end of American exceptionalism. At the time of writing, the Financial Times, still the market’s newspaper of record, is running a front page as well as a comment section article on exactly that topic. Despite President Trump’s bluster, there is a strong sense that, like it or loath it, the current administration’s policies are at some level driven by a realisation that the unipolar world of American dominance is giving way to a multipolar one, where the US can at best hope to be first amongst equals.

In investment terms, the end of US economic exceptionalism can be interpreted through the performance of the country’s stock market, itself a partial if not perfect reflection of its economic might and technological advantage. The graph above shows the sharp dip in the value of US equities as a percentage of world capital markets. The point to note however is how high this number still is relative to America’s portion of global GDP (somewhere around 20%).

While falling bond yields may show a recession starting to be priced in, the fall in US equities while other equity markets perform strongly (Europe especially) indicate a switch in asset allocation away from the US. That the dollar is falling as US equities fall confirms this flow of funds analysis. Money may well be going home as the world of tariffs and trade wars puts another nail in the coffin of the era of globalisation that followed the end of the cold war.

The wisdom of rotating from one equity market to another right now is however debatable. Not only is the bond market hinting at a slowdown, at last Wednesday’s FOMC meeting, the US Federal reserve downgraded US 2025 growth estimates from 2.1% to 1.7%, while raising unemployment estimates from 4.3% to 4.4%, as well as raising core PCE inflation predictions to 2.7% from 2.5%. Low growth, rising unemployment and rising inflation is kind of what the stagflationary 1970s looked like, and this was not a great time to be long equities.

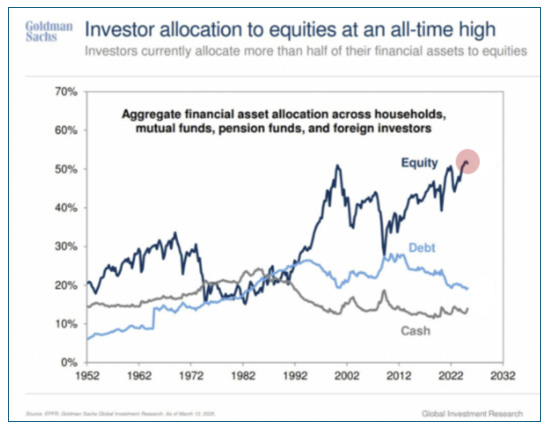

While a recession is not yet a certainty, and while the huge US primary deficit pouring cash into the economy makes a fall in nominal GDP less likely, the graph above, showing how heavily investors are still allocated to equities, is a concern in the context of fully-valued markets, especially with so much cash still parked in the most over-valued market of all, the US.

Given where markets are currently trading, a lot seems still to be riding on the hope that the Trump tariffs won’t be that bad. Headlines on the 22nd March suggesting that the April 2nd ‘liberation day’ reciprocal tariffs will be ‘more targeted’ have seen stock market futures trade up sharply3.

Perhaps, after a sharp sell-off, markets are due a bounce. This is particularly true when technical factors including volatility selling, the decaying of downside protection as well as the positioning of quantitative investors such as CTA’s (commodity trading advisors) is taken into account.

For those whose investment horizon stretches back only as far as say 2010 (ie post the financial crisis), every dip has been a lucky dip to be bought with vigour. It seems that retail investors have been doing just that over the last quarter. Whether this turns out to be a smart bet remains to be seen.

In an excellent article in Saturday’s Financial Times, economic historian Barry Eichengreen highlights how, with respect to the dollar as a trusted reserve and trading currency, President Trump has taken, “only a few months to weaken if not destroy those relationships and that reciprocity” (FT Link).

Front and centre is the debate about the so-called Mar-A-Lago accord (see Market Depth link above for a more extensive discussion). Using tariffs both as revenue-raising and negotiating tools, while weakening the dollar and potentially swapping shorter-dated US Treasury debt for 100-year zero-coupon bonds is a strategy which not only seems ‘bold’ in the extreme, but could potentially be highly destabilising.

The issue here is that much of the trade and tariff (as well as the dollar and bond market) policy being discussed involves some huge assumptions. First, that other countries won’t retaliate in kind, and that this retaliation won’t severely affect the US economy. Secondly, that weakening the dollar won’t unleash a fresh round of inflation, especially in energy prices. Finally, that messing around with the long end of the bond market won’t cause a large rise in yields which could take down the credit markets, which have so far been pretty stable.

While investors may be comfortable with a buy the dip strategy, and while the Fed’s decision to cut its quantitative tightening volumes to just $5 billion per month for US Treasuries (per March’s FOMC meeting) may hint that it’s business as usual with respect to the Fed put, fund flows suggests that more fundamental changes in asset allocation are afoot, reflecting what increasingly seems to be a changing of the world economic order.

The extraordinary pace at which the current US administration is pursuing its agenda is clearly taking markets by surprise, and this in itself should encourage investor caution. Trump has less than two years until the mid-terms, and thus speed seems to be of the essence for his reforms.

While clearly not the same process the Russian economy underwent in the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the effect on the status quo in terms of trade and diplomacy of current US policy could well be described as a sort of shock therapy. They say in markets the trend is your friend, but unfortunately for 2025, the trend seems to be extreme uncertainty. Maybe that dip isn’t quite so attractive after all.

John Maynard Keynes, A Tract on Monetary Reform, 1923, p10.

Ibid., p15.

Josh Wingrove, Trump Plans His Tariff ‘Liberation Day’ With More Targeted Push, Bloomberg, 22/03/2025.