Safety in numbers? Doubting the data goes mainstream.

Thanks to President Trump, questioning official statistics is no longer just a hobby for the tinned food, guns and ammo types.

There is a long history to the sentiment, often attributed to British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, that there are, “lies, damned lies, and statistics.” Most recently, President Trump has suggested that the negative 250k revision to the May and June Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) job data was “rigged” to make him “look bad”1.

Not content just with throwing his toys out of the pram, the President went on to sack BLS commissioner Erika McEntarfer. While her replacement has yet to be announced, one now has to assume that they will be under pressure (or assumed to be under pressure) to make sure future statistics are White House friendly. CPI Inflation data is out this week, and this statistic is another one produced by the BLS. An unusually-low print to put pressure on the Fed to cut rates? Let’s see.

There is a real story behind the revisions to the BLS’ employment data. The payroll survey involves questioning 121,000 businesses of various sizes across the US on their employment activity. Within the first month of the survey, 68% of companies respond. Due to delays, particular at smaller businesses with more limited HR resources, the BLS leaves the survey open for another two months. According to William Beach, former BLS chair, the response level rises to 83% in the second month and to 94% by the third and final month2.

This new, delayed data - rather than a Democrat plot - is likely in part responsible for the recent revisions. One might say, especially given the higher input from small businesses in later iterations of the data set, that the effect of tariffs or the lack of clarity over the future direction of Trump’s tariff regime may be affecting small businesses more immediately and more negatively than bigger firms, but future data will likely confirm or negate this hypothesis. Sacking the person in charge of the data is probably not the most grown-up response.

There are of course other issues in acquiring and processing employment data. 2024 saw a divergence between the payroll survey (of businesses) and the household survey (of what the BLS describes as 60,000 ‘eligible’ households), with the latter showing a less sanguine view of employment trends in the US economy.

Investment Bank ABN Amro suggested at the time that it was possible either that the effect of illegal immigration boosting employment was not showing up in the household survey (hence it being gloomier), and/or that the birth/death model in the corresponding payroll survey (which adjusts data for the creation and winding up of companies) may have gone awry for a number of complex reasons3.

Either way, the discrepancies weren’t overtly political, even if doubts were being raised about the direction of employment in an election year. A sensible macro analyst would for example use the poor household data as just one input into an argument against a high US equity portfolio exposure. Again, there’s no need to sack anyone.

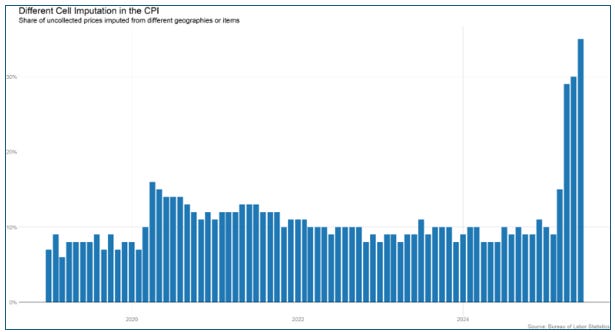

There have also been some questions raised about the BLS’ inflation data. The graph above shows the number of CPI items which are now subject to ‘different cell imputation’, ie: not directly collected by a BLS agent but inferred from other items or geographic areas. Part of the problem appears to be a staff shortage at the BLS itself, possibly but not necessarily due to Trump administrative cut-backs. The upshot is that economists are (and should be) questioning the veracity of some of this data, even if the cause is not as overtly political as perhaps President Trump is insinuating4.

There are therefore two issues at stake here. First is the slavish reliance on numbers and statistics within the economic profession and within markets more generally. The physicist Lord Kelvin once said, “When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it…your knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory kind.” While econometrists may have taken this maxim to heart, it clearly shows a lack of common sense when it comes to the mirky world of employment and inflation stats.

This sort of common sense caution about economic statistics was most clearly and extensively stated way back in 1950 by Princeton mathematician and economist Oskar Morgenstern in his classic ‘On the Accuracy of Economic Observations’. Not only does he address the issue of statistical accuracy more generally, his book dives into the detail of what are still issues of controversy today - specifically problems around BLS’ surveys and data acquisition more generally.

Professor Morgenstern in fact suggests that while unemployment data is presented to the nearest thousand, a better approach would be to the nearest million. For data like inflation, he suggests that an standard error of plus or minus 10 to 15% would be appropriate5. This may sound crazy given the craving for accuracy in today’s markets, but when you realise this chap had his PhD supervised by Ludwig von Mises and that he worked with John von Neumann on the foundations of game theory, then one ought to take his views pretty seriously because he was a very serious thinker indeed.

The second and more general problem is the credibility of economic data and decision making in a country where it is known that the executive is comprising the independence of national institutions via the hiring and firing policy of the officials who work at them.

With respect to the BLS, not only will its independence be questioned in future, but response rates to surveys may well fall, while it also likely the quality of recruiting will be compromised, as will respect for the methodologies those employees use, especially if it is felt that procedures are being chopped and changed for political reasons6.

Everyone knows that the incumbent holds the whip hand when it comes to juicing policy to help win the next election. This is particularly true with economic policy, where tax cuts or spending giveaways are used to swing voters at the polls. This is nothing new.

However, when the already imprecise world of economic statistics becomes overtly politicised, the ultimate casualty is the sovereign itself, in the form of a weaker and less trusted currency on the one hand, and correspondingly higher interest rates on the national debt on the other. Given the current state of its finances, this isn’t a road America really wants to be going down right now.

Christopher Rugaber, Trump says he doesn’t trust the jobs data, but Wall Street and economists do, Associated Press, 05/08/2025.

William Beach, former BLS Chair (2019-2023), Bloomberg ‘Oddlots’ interview, 04/08/2025.

Roger Quaedvlieg, US - Resolving the Labour market puzzle, ABN Amro, 19/06/2024.

Matt Grossman, Economists Raise Questions About Quality of US Inflation Data, Wall Street Journal, 04/06/2025.

Oskar Morgenstern, On the Accuracy of Economic Observations, Princeton University Press, 1950, pp8-9.

Erica Groschen and William Beach, Trump’s war on data will do lasting harm, Financial Times, 06/08/2028.